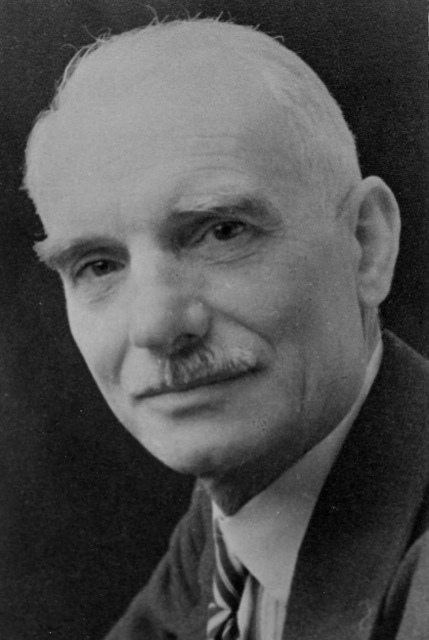

Charles Balbis’s family in hiding, 1942

In February 1942, some months after the Coakleys had settled in England, Gabrielle Coakley’s father, Charles Balbis (62), had gone into hiding in the French Pyrenees, with his wife, daughter, Jewish son-in-law and two infant grandsons.

Getting word that his landlady in Ville d’Avray wanted to rent the house he had occupied prior to the war, Balbis needed to remove and store all his family’s belongings. With no time to apply for and obtain a laissez-passer, the permit required by the Germans to pass the Line of Demarcation, he decided to cross it once more, clandestinely. With only a change of clothes in two suitcases, some toiletries and a Michelin map, he returned by train to the village and the café where he had rested with his daughter after they’d been smuggled to the free zone and before continuing south to Nice. Inside the café, he applied to the boss to help him find someone to smuggle him back into the occupied zone.

Told to wait, a French policeman arrived in the café and checked his papers, wordlessly. Balbis assumed he was suspected of being a squealer who would reveal to the Germans the secret crossing; however, a passeur and his wife finally arrived, both barefooted. In the dark, they walked to a location on the bank of the river, where the passeur carried Balbis on his shoulders while the passeur’s wife carried his belongings. After crossing the Allier River in silence, Balbis was directed to cross a muddy field. Arriving on the other side in the pitch black, he decided to take the deserted road instead of crossing another muddy field. With four kilometres to go to St. Pierre-le-Moutiers, where he planned to take a train to Paris, Balbis continued walking but was stopped, within a kilometre of St. Pierre, by a German officer who demanded to see his laissez-passer.

Noting Balbis’ muddy shoes and trouser bottoms, the officer knew Balbis had crossed the frontier. Thinking it pointless to deny, Balbis remained silent. The officer demanded how much Balbis had paid to cross and added that he knew someone who paid 5,000 francs, giving Balbis the idea that the German might be bribable. They came to a closed café/tobacco shop that the manager opened for the German officer who purchased cigarettes and two drinks, both of which he brought to the table where Balbis sat, and to Balbis’ surprise sat opposite him. In the light, Balbis saw the German was about thirty. He offered to pay for a second drink, but the young German explained he was on duty and could not accept, making Balbis grateful that he had not tried to corrupt the man.

They continued in the dark until Balbis tripped and the German offered to carry his suitcases. He insisted and Balbis allowed him the one that did not contain his false-bottomed shaving brush in which he had concealed some addresses. With the officer walking ahead of him, Balbis pretended to drop the suitcase, causing it to spill its contents. He retrieved and hid the shaving brush in his raincoat pocket.

At midnight, they arrived at the commandant’s post, where the officer fetched a bad-tempered German in pyjamas. The Germans spoke and then began to examine Balbis’ suitcases. Paying particular attention to a notebook listing the contents of his house, including a list of books, the commandant became agitated upon reading the name Tolstoy and accused Balbis of being a communist. Laughing, Balbis pointed out the name was in a list of authors, Victor Hugo, Shakespeare etc. Disappointed, the man asked for Balbis’ identity papers. The old man continued to conceal the shaving brush in his raincoat pocket.

A similar shaving brush to the one Balbis describes can be seen in the Musée de la Résistance in Besançon.

The rest of the night, Balbis spent sitting on a chair before a wooden table. At dawn, he said he had to go to the toilet where he removed the note from his shaving brush, tore it to shreds and threw it into the toilet. He spent the rest of the morning sawing logs within sight of a sentinel and a bridge leading to the free zone. Then he fainted and was carried to the sentinel’s post where he revived and was brought buttered bread and hot coffee, his first meal in twenty-four hours. Thereafter, he stood to resume his labours but was not allowed to do so. Sometime later, a large ruddy man wearing a German policeman’s uniform arrived, spoke to the sentinel then, making a cut throat gesture, he approached Balbis and indicated a car nearby, in which they headed for the former prefecture in Nevers. There, a civilian spoke in German to the policemen and then to Balbis in French. The interpreter required a statement as to why Balbis crossed without a permit and advised him to place considerable emphasis on the fabricated story he had told the German officer about his mother being gravely ill and requiring Balbis’ immediate presence. Understanding the interpreter’s sympathies, Balbis followed his advice and thanked him. From there, he was taken to prison and relieved of his suitcases and identity papers. He feared that his daughter’s name on one of his identity papers might lead to the Germans making further inquiries as to her whereabouts, since she had been interned in Frontstalag 142 and had left Paris while still under house arrest.

What follows in this account is a description of the other prisoners, their meals (inedible black bread, rutabaga soup and ersatz coffee like elsewhere) and life in prison. He records, in detail, the stories of his co-detainees and the reason for their incarceration. After one month’s detention he was set free. His family knew nothing of his whereabouts.

To tell more would be to give away the plot. Balbis’ account will appear in my book,

From Paris to London via Frontstalag 142 in both the original French and my translation. Stay tuned!

Madeleine de Bruijn-Beeching

Blotzheim 26 February 2013

You can read about the Coakley’s escape from France by clicking here: Meg, Lillian, and Gabrielle Coakley: “Bang! Bang! Bang!

Comment on the story here.