You can read the previous part of Elly’s story here: War Years: Troyes, reunions, and other events

Marseilles

The city had always been a crossroads for people from all over the world. Now it was the last resort for refugees from the Nazis, who occupied most of Europe. The other part of France was openly part of Germany, but the Nazi officers were here as well. One day while walking with Mother on the Canebière I froze and started to shake and cry and Mother asked what was wrong and I pointed to a balcony on one of the large hotels, and sure enough, several of them were standing there, in full uniform. Yes, they were there all right.

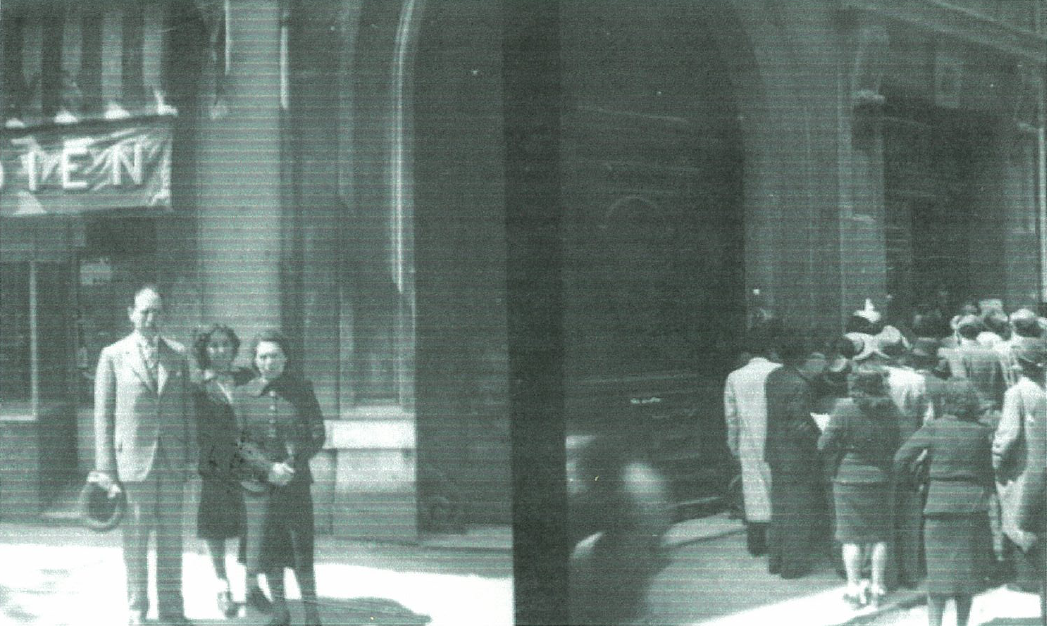

When we had reached Marseilles in June 1940 we spent the first night with Gerty and I sharing a bathtub, sleeping head to toe. Eventually we found, in the old harbour area, a small room on the top floor of a dilapidated hotel. The stairs sagged, the doors did not close and when it rained the ceiling leaked into the middle of the bed my sister and I shared. Mother occupied the other bed and aside from the table, a chair and a sink in the corner, our room had nothing else to offer but cold draughts. For Gerty and me it was a time of endless rounds looking for kerosene for our tabletop burner, waiting in line for bread or a few potatoes, always carefully fitting in those errands around the main activities of the day.

But the first thing we all three had to do was the daily report to the police to have our papers stamped, which validated us for the day. Then came the visit to the American embassy to see whether our name was on the list of visas granted that day and then to the steamship line for the listings of departing ships. It was a constant struggle to have all parts of the jigsaw puzzle that spelled “Life” fit together: the American entry visa, the French exit visa, the Martinique transit visa, the steamship ticket and one or the other of these was forever expiring when the others came through. We all lived on hope and rumours and very little food.

Unless you were rich enough to eat in a hotel restaurant catering to those who could pay, you were hungry, all the time. We were among the latter group. We had a little burner which ran on alcohol, if we could find some, and that was another daily activity. One day, while walking to do our chores, we ran into the beautiful woman Mother and I had met in Paris where we had stayed for a while. She went to see Mother and again asked her to allow her to adopt me, but Mother refused again, not that I would have been willing. However, I was willing, and Mother agreed, to have her take me to lunch at the hotel where she stayed with her husband and her lover. I was delighted to get a good meal, and was so excited that I fell down the stairs in the lobby, because I had just noticed a famous French actor who was about to leave. Well, I was only 15…

One day our father called for us to come downstairs, which we did. We rarely saw him since our parents had been separated for some years. He opened his jacket and took out a container of milk for us, something we had not seen for months. Mother, Gerty and I sat in our room, looking at the milk and talking about what to do with it. We decided we could not just simply drink it, it was far too good for that.

We agreed to go on a forage the next morning, looking for something to cook with that milk, maybe some cereal… we went to sleep with happy thoughts of what we might be able to eat the next day. Early in the morning we got out of bed eager to start, only to discover that during the night the milk had turned sour. So much for the milk story, and I for one never forgot the lesson: if something good comes your way, take it, be grateful and don’t wait for something better.

We were always hungry, always, and everything was rationed, and we had so little money, we never had enough to eat. One day Gerty and I went to see what we might find with our ration tickets, and the delicious aromas of a certain market drew us in. We looked around but there was nothing we could afford. But while the owner was occupied with another customer, I saw a smoked eel hanging from the ceiling. One, two, three, I reached up, grabbed it, pulled it under my jacket, and the two of us ran fast as we could out of the market and around the corner. What a feast we had that night!

We were not allowed to work, nor could I go to school, and we managed by Mother doing what she could in making and selling the handmade lingerie which had earned her and us a living for many years, Gerty and I doing the finishing work on the inside seams. In addition, Gerty from time to time found work in some small store, but invariably the employers would end up not paying her. Perhaps they might give her some food if it was a grocery store and one of my saddest recollections is connected to such an event. She had been offered a job selling candy in a store in the Arab Quarter in exchange for a few francs.

Within a week the owner’s interest in Gerty had become not only clear but unavoidable and enticements became entreaties and then demands, and she had to leave. In payment for her work she received not money, but a bag of halvah, that ultra-sweet concoction from the Middle East. We were hungry all the time and when Gerty came home the three of us shared the halvah as the meal of the day. Sweet, rich, cloying we ate it slowly to make it last and then talked of looking for other work the next day. Soon after the halvah was eaten it started to cause severe stomach pains and finally, despite my efforts to keep it down, it came up with many tears.

The nights were filled with fear for all of us: the French police would encircle a block and search every room in every building, checking the documents to make sure the person was legal and not sought by the French or the Germans. One night we had a big scare. The police took all three of us in to their station and told us to sit and wait. That was nerve-wracking already, but when two policemen came and took Mother away without telling us anything, that was agonizing. She was gone for several hours, we knew not where, but finally came back to the waiting room. It seemed that she was accused of being a Resistance fighter but in the end they showed her the photograph of a woman who used Mother’s first and last name, and who resembled her, but only a little. They let Mother go. It’s amazing to remember how much and how often we cried.

Every night the blaring of police vans kept everyone on edge and there were almost always some people who did not have any papers, or who were in the Resistance. We usually stayed in the hotel room from the evening hours until morning. A few times I went out to join demonstrations on the street, to my Mother’s despair. I was then, and to a large extent stayed, stubborn and unwilling to buckle down to enemies.

Read the next part of Elly Sherman’s story, War years: Marseilles, and two miracles

<

Comment on the story here.