You can read the previous part of Elly’s story here: War years: Marseilles, and hotel days and nights

Anxious days

We were called to the police station and told to report in five days to the French concentration camp in the Pyrénées, a camp which led to Auschwitz or one of the other death camps. Mother was ill and devastated. Gerty and I decided to get advice from Uncle Otto. Well, he was not really our uncle but a Viennese refugee alone in Marseilles after losing his wife and two daughters about our age. One never asked for details of such events knowing it was a most painful subject. It was a time when almost everyone had tragic events to deal with and one never asked “how” or “why”.

Uncle Otto had taken Gerty and me under his wing and had given us permission to come to see him in his hotel if we were very very hungry and had nothing to eat, and he would buy us a cup of watery chocolate and a breadstick at the café downstairs, and this would often sustain us for the day. We tried to limit calling on him for this, so as not to impose or even worse, to lose the prerogative. He was always kind to us. Perhaps we reminded him of his lost children. He sometimes told us he had a “friend” in his room – and of course we understood what that meant – and if, when we knocked at his door, he told us to go downstairs and wait, we dutifully did so.

When we told him that we had been called to report to the camp, his advice was straightforward: “You are both young and attractive,” – my sister was 20 and I was 15 – “Go to the Chief of Police, do what he wants, and this way buy your way out”. When we finally understood that we were to sit at the edge of the desk, raise our skirt over our knee and smile seductively we finally got the point and left. [...]

But we were also assailed by doubts: we remembered the many stories of wives who, trying to obtain a husband’s release from the Gestapo, tried the same route and when it was over were handed the husband in a jar containing his ashes. How could one possibly trust a chief of police to keep his word any more than one could not trust the Gestapo? By the time we returned to our hotel room, still not having settled who was to go see the Chief of Police, Mother had recovered, had cabled her brother in New York, and with the money he sent we bought our way out.

A couple of weeks later we were again called to report for internment, but when Mother went to see the Chief of Police he told her that the Germans had become much more demanding, and that the French had to turn over their quota of Jews. Bribes would no longer work and the three of us had to report within two days. The amazing part of all this was that he was honest enough not to take the bribe first.

We were desperate. In the two days remaining we were frantically trying to get everything together for our escape. The United States visa was the most difficult and the most unlikely for us to receive since we had no papers of any kind, no citizenship, and no residence. We had been citizens of Austria until the German take-over, and when the German consulate offered my parents German citizenship, they refused it. We were never able to obtain French citizenship. My father did apply, but he was over 40 years old, and he had no male children, which meant there was no-one to serve in the French army, so citizenship was denied. We also had very very little money. We were in a hopeless position.

Mother again begged me to leave through the Quakers’ program for children, as she had several times in the past year, and I again said I would not go. Mother was truly and terribly upset, repeating that the Quakers had saved many children, and I would be one of them. But that would mean leaving without her or my sister and I said that, if I were saved and they did not make it, I would hate what I would see in the mirror for the rest of my life. We would either all be saved or none of us would be saved. Oh, my Mother had a hard time with me, she thought at least one of us would be saved, but I was stubborn and too big for her to pack me off. And that was when we were handed two miracles, and all three of us were saved.

Of course we were only three of many who were saved by those unknown wonderful people who often risked their own life to save a few Jews: they should be remembered and thanked every day, but most of them remain unknown to us who benefited from their human kindness.

Two days and two miracles

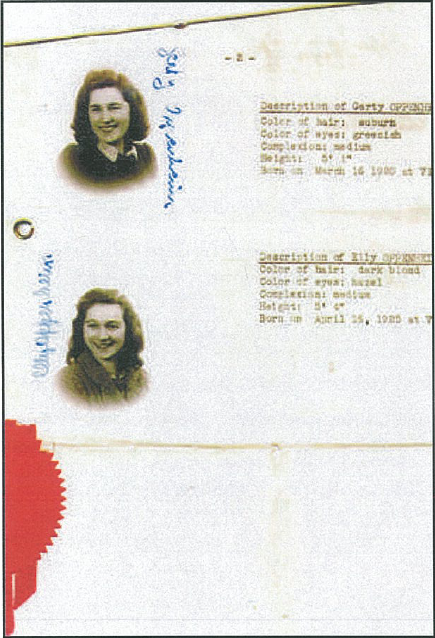

Gerty and Elly on the family’s “Affadavit in Lieu of Passport”. Issued by Hiram Bingham on 3rd May, 1941

It was not until many years later, in 2005, that I found out who had provided us with that precious visa to enter the United States. I received an email of an article which mentioned the role Hiram Bingham IV had played in France during the war years, that he had been Vice Consul in the United States Consulate in Marseilles and had saved over 2,500 people, many of them Jews, who were to be remanded to the German concentration camps. The arrangement between Vichy France and the Germans as that the French Police had to “Surrender on Demand” everyone named by the Nazis.The name Hiram Bingham seemed familiar, and I looked through the documents which had belonged to my now-deceased Mother. There it was: the original document granting the visa to my Mother, my sister and me, signed by Hiram Bingham, the red seal partly missing, the red ribbons a bit frayed but still there. It would be difficult to explain all the various feelings this has aroused, even now. I am so deeply grateful to the man who took such chances in helping us and so many others.

And he did take chances, and doing what was considered an illegal act cost him his career. He was one of the heroes of that time. Two days after he had given us the visa he was removed from Marseilles and sent to Argentina where he served several years but he never was granted any advancement in the consular service and finally resigned. Those two days before we were to report to the camp at Gurs. What is the meaning of two days? How do you count? All the events of that time came back in a rush, accompanied with many a tear, and a deep wish that my Mother and my sister could be here to share in it.

The past is ever with me, and although we were spared the worst, we were deeply aware of the fate of the ones who were not as lucky. Often I also went through deep depression, feeling, “why me??”, that feeling strong in this sense of “why was I saved? What must I do to merit this? How can I repay having received the gift of life?” But this gift, the gift of Hiram Bingham and all my gratitude, is in the tears of my memories and in the laughter of my life it granted me, and in never forgetting.

There still remained another miracle to be solved for me: how did we obtain the tickets for the ship?

Read the final part of Elly Sherman’s story, War years: Who gave us the tickets, celebrating our departure and why it was not so good

Comment on the story here.