You can read the previous part of Philips story here: La Rochelle

The end of our journey

On 23rd June we had our first rain, and it got heavier. My father recorded that we cycled 103 kilometres that day, and stopped at a farm just short of Tartas. We would reach Bayonne the next day, the last town of any size before the Spanish frontier. It was still wet next day, and we duly reached Bayonne.

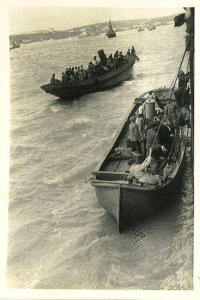

A seaman from the Baron Nairn helps Philip’s mother up a ladder onto the ship. The S.S. Baron Kinnaird can be seen a short distance away

My father made his way to the Mairie (Town Hall) in the Place de la République, and the whole square was ‘surrounded’ by French soldiers with their rifles. My father was able to see a functionary who told him that the British Consul had left that morning for England, and that, whilst he was not senior enough to know officially, he thought that the Mayor was signing the surrender document for Bayonne to be handed to the Germans. The man said that our best hope was to carry on to the small sardine fishing port of Saint Jean de Luz, some 20 kilometres further west. We had left very early that morning, so we remounted – but not for long. All the time since the previous day the atmosphere had become heavier and heavier, and clearly a storm was developing, for the air was very sultry indeed. We hadn’t long to wait: some cracks of thunder and shafts of lightning provided the ‘Overture’, which soon was followed by the ‘cannonade’ of the 1812 overture! Down came the stair-rods, which soon changed to a very obtuse angle, because as often happens in a storm, a tremendous wind got up, and so as not to be outdone, it turned into a full scale gale, and one could taste the salt from the not too distant Atlantic Ocean. It soon became obvious that we would have to dismount, because first my mother, then my father who had put his briefcase in the ‘gap’ of his cycle frame, was blown off. I recall my mother saying to my father “Shouldn’t we halt for a bit?” to which my father in a firmly determined voice barked “No! We have to reach St. Jean”. So on we went, – remounting at times, but mainly I recall walking and pushing our bikes. Within minutes we literally were soaked to the skin, the rain squelching happily from our shoes. I so remember passing some French people who were sheltering in some sort of bus stop type little cabin; they had clearly heard our English voices, and the husband said to his wife “Mais ils sont fous, ces Anglais!” (But these English are mad!) – an inversion of Noel Coward’s famous song!

I recall seeing the rainwater pouring off my father’s nose and then being blown in a great plumed spray by the whipping wind. I think St Jean de Luz is about 20 kilometres from Bayonne, and I reckon we walked most of them, pushing our cycles.

Unknown lady (I rather like the hat!), my mother, and me, eating from the packet of Biscottes we had managed to buy en route

Having been our indispensable companions for all those days (13 days from leaving our Town Hall paillases) my father went to sell our cycles. In Paris when we left, cycles were worth a king’s ransom – but I think my father got just Frs 50 each (less than 101- per bike.) We got some food to eat standing up and returned to the station. I then took a little walk to the harbour wall, where I saw about 10 or 12 French ‘Poilus’ (French equivalent for ‘Tommies’). They each threw their rifles over into the sea, followed by their ammunition pouches. Young as I was, I was disgusted, and thought to myself that any platoon of British soldiers who had got separated from their Units would be ordered by the Senior NCO to “Get down either side of the road, and when Gerry comes, let him have it, and bayonets when we run out of ammo.” I was appalled, at this blatant cowardice of French soldiers.

And so, back to the station. I was surprised how some refugees had suitcases among their possessions — I supposed they had managed to come by car. During what there was of the night, one elderly English lady kept calling out “Popsy, where are you Popsy?” “Has anyone seen my little Popsy?”

I suppose we dried out to some extent on the hard tile floor during what there was of the night. Next morning early – 3.30 AM to be more precise – the Naval Officers ordered folk to go down to the jetty. Although the previous day’s storm had spent itself, as is always the case, the sea has a longer memory, and there was a considerable swell running in the harbour. The sardine vessels were nice looking little boats I thought. We were early in the queue, and it was not all that long before we were directed to a boat. There weren’t too many per ”shift” – about 20 at a time, I think. Our skipper pulled away and headed for one of the two ships anchored in the harbour. The boat soon responded to the heaving seas, and the skipper had to exercise some pretty good seamanship to get alongside the cargo vessel – the latter was lightly laden and so seemed to tower over our little ship. On the first attempt to come alongside, a wave caught our boat and it hit the cargo ship a hefty wallop against its hull, splintering the wooden ladder the crew had somehow managed to lash to the ship’ s side – so our skipper moved away and circled the bigger vessel until another ladder was let down. Our man tried again same result, so the crew then let down a rope ladder. Our valiant skipper again made an approach and that time his mate was able to grab a rope the crew had let down (and somehow managed to fasten below the water line) so that the mate was able to haul our boat against the big ship and keep it there. Then began the task of getting refugees on board – not an easy task, with the little ship rising up and down several feet, on the swell, whilst the skipper somehow managed to vary the revs on his engines to try to keep his boat “on station”. We got on board, and a rope was fastened around our bundles and hauled up on to the deck. The cargo vessel’s crew were marvellous – where people were too frail, a sailor came down, put the person on the ladder and “shoved them up” : unceremonious but it worked! A sailor even came down to bring “Popsy” up on deck. Only the British would do this, surely (“lls sont fous, les Anglais”).

Gradually the little ships went back to fetch more refugees, but we saw some whose skippers finally gave up, and returned to the jetty still fully laden, perhaps having damaged their own boats. My father’s General Manager was one such ‘unlucky’ one, and in due course spent the war in an internment camp, being too old to be sent to one of the ‘Hard Labour’ camps.

Comment on the story here.