You can read the first part of Philips Story here: ’1940 the fateful day’

Midsummer

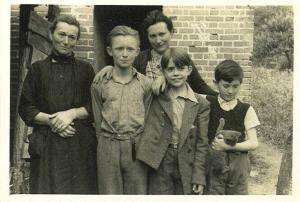

Derek and Philip (centre), with a grandmother, her daughter and grandson at their farmyard, where Derek and Philip stayed the night.

We left Fontainebleau at 5 am; very early starts were a feature of our journey, but it was midsummer and the sun was well and truly up. I recall that fairly soon after leaving Fontainebleau, my father decided to take to the minor roads, for the more major roads were continuing to be blocked by bottlenecked cars & camionettes of French refugees, which were making little or no progress. Once the occupants of a nice Citroen saloon car offered us the car and petrol vouchers in exchange for our cycles! Another reason for taking to the side roads was that one morning en route towards Orleans, an aircraft flew over quite low and suddenly we heard machine gun fire – it was clearly strafing the columns of refugees as a bit of fun; a little later another aircraft flew over and we abandoned our bikes and dived for the ditches, but it turned out to be ‘one of ours‘. We had to pass through Orleans and there I recall seeing people wounded, some on stretchers, bandaged and bleeding, presumably victims of the strafing. Thereafter it was minor roads all the time. At one stage we were passing Villacoublay airfield, and I saw a flight of three or five French Fighter planes getting ready for take-off. As a small boy I naturally stopped to watch them, despite my father’s calls to “come on son”. To my astonishment, the fighters began their taxiing run, and one assumes at the command of the Flight commander, the pilots pushed forward the joysticks and each fighter’s propeller hit the ground causing the aircraft to somersault forwards and land upside down; the pilots slid back their cockpit hoods, let themselves down and that was it: aircraft ‘un-serviceable’. Even at my young age I was appalled to see such an example of cowardice, and this was at a time when the French Prime Minister – Paul Reynaud, I think – was beseeching Churchill to send more RAF Fighter squadrons to France. I am sorry to say that l was to see further examples of cowardice later.

On the minor roads we were able to make much better progress; the question of finding food was at times a problem – sometimes it was not difficult to buy a tin of pate and bread from shops, but at others there was almost nothing to be had, so we just went hungry. Not infrequently this shortage was because convoys of French troops, fleeing from the advancing Germans, had ‘raided’ the shops and pretty well stripped them bare – and the shopkeepers were pretty incensed that their own troops were looting, in effect. I remember thinking “why are the French soldiers running away instead of trying to fight the Germans?” Nearly all the time, local folk in villages or at farms would say “Les Allemands ne sont pas loin”, i.e: “The Germans are not far behind”, which dispelled any feelings of fatigue which might be affecting us. It was cycling, cycling, all the time, in extremely hot weather the further south we got.One day, which may have been exceptionally sunny and hot, we reached a small town, and dismounting I felt terribly giddy and the skywas whirling round above me. My mother deduced I had got a touch of sunstroke. We were on a verge besides some country houses and a large lady came out; my mother explained the problem, and this lady exclaimed “Oh mon pauvre petit” (Oh you poor little mite), brought out a chair from her house, sat me on it and went indoors. In no time she was out with a bowl of steaming hot water and added a lot of brown powder to the water (mustard, I discovered) and promptly plonked my two feet in it. I recall feeling that I did not want my feet plonked in very hot water smelling funny, but my mother was uttering thankful noises, so l put up with it. Suffice to say that I soon felt a lot better, and on we went.

Vive l’Angleterre

There were times when my parents allowed only my brother and myself to try for food at the shops, because there was in places immense anti-British feeling, and my parents did not have accent free French. I recall once hearing two French people asking “Ou est la Royal Air Force?” (i.e. ‘Where is the RAF’?) so we kept our nationality to ourselves. On another memorable occasion, my father must have stopped to ask a French farmer some directions – immediately there came a response: “Mais vous étes Angiais?” – “But you are English?” whereupon he ceased his labours and insisted on taking all four of us into his farmhouse, and introduced us to his wife -”Ces gens sont des Angiais qui tâchent de retourner a l‘Angleterre” – “these people are English endeavouring to get home to England” – “Il fault leurs donner dejeuner” – “We must give them lunch”. Without the slightest hesitation Madame got to work and the table was laid. Monsieur produced an Apéritif, and in no time we were at the table consuming a marvellous ‘potage’ of vegetables, piping hot. The plates were duly wiped dry with nice lumps of fresh bread, ready for madame to serve the main course of a meat casserole and vegetables, whilst Monsieur alternated between refilling my parents’ glasses with red wine and giving full rein to his opinions of the ‘Salles Boches’ (an expression dating even from the 1870 Franco-Prussian War meaning ‘The dirty Huns’) and “Les Anglais merveilleux” (the marvellous English). The main course finished (and we were all struggling a little, having become rather accustomed to short rations often eaten on the hoof) we again wiped clean our plates, turned them over to reveal the quite deep rim on the underside, enabling Madame to decant into the depression a wonderful syrup with large black cherries — scrumptious! (In later years I told my daughters that we then wiped the plates clean again thus enabling Madame to put them back on the dresser shelves ready for the next meal!) Monsieur then insisted on pouring my parents an enormous glass of brandy, described modestly as “un petit digestif”!! About three hours later, my father with an anxious look at the time, managed to lift himself from the table. Then came the ‘Piéce de Résistance’: having convinced the kind farmer that we must be on our way, he proceeded to insist that we take one of his suckling pigs with us, because he did not want “Les salles Boches” to have them – my father explained we just could not take it on our cycles, and eventually he conceded it would be difficult, but my father had to exercise all his diplomacy to persuade the farmer without appearing ungrateful. So, several (actually probably three in all) hours later we remounted and took to the road, my parents executing a slightly less than steady course along the hot French country roads, with the ever more faint calls of “Au revoir” and “Vive l’Angleterre!” What a lunch: it charged us up for days I think!

Read the next part of Philip’s story: “Summer 1940. La Rochelle”

Comment on the story here.